Is all literary fiction like this?

I recently listened to the audiobook of Paulette Jiles’ Chenneville. Jiles is the author of News of the World, which was adapted into a feature film starring Tom Hanks. The score for that film, by James Newton Howard, is in my Western Writing playlist, which led me into a brief curiosity about Jiles’ work.

The premise is this: A Civil War veteran, John Cheneville, recovers from a head wound in a field hospital in Virginia. He returns home to St. Louis as inheritor to his family’s plantation. While he recovers his faculties, he learns his sister, husband and child have been murdered in a nearby county, and there is a suspect by the name of Dodd, but officials have refused to investigate. John decides he must track down this man and kill him.

There’s a lot of dramatic tension to mine there, like any classic Western, but Jiles writes Literary fiction dressed in boots and a wide-brimmed hat. More to the point, she writes Literary travelogues dressed up in a Western’s clothes. Protagonists in all her novels must travel across the bleak landscape of the American west, overcome myriad challenges along the way, and grow as a person if they want to survive.

Based on the logline and back cover copy, it is a Western that leans heavily on a revenge plot. That means a promise of gunplay, though the cover (a portion shown above) does not show anyone in a classic gunfighter pose. It shows a guy on horseback amidst an open landscape, bathed in the glow of sunset, forecasting some sort of closure, but this sunset is soft, gentle and warm.

Before I get into spoiler territory, I wanted to mention a Lit Fic book I actually really liked.

Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter

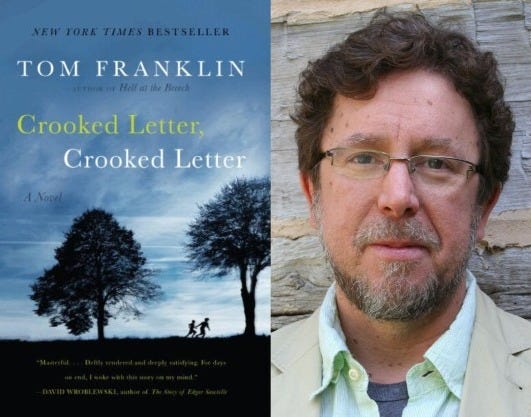

When I was exploring potential MFA programs, one of the more promising options was The University of Mississippi, otherwise known as Ole Miss. Tom Franklin is one of the instructors there, and based on the vibe I got from the program, he was one of the first whose work I checked out.

Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter uses many of the trappings of a mystery, but from the outset you can tell it’s not really about the crime. The book is about Silas, a small-town constable forced to return to where he grew up and investigate a new missing-persons case that resembles one from ages ago in his teen years. His childhood best friend, Larry, is by all appearances to modern readers, autistic, but the book is set in the late 70’s, so he’s just the weird guy who the town ostracizes. In High School, a girl who he took to a dance disappeared, and he is long-suspected of having something to do with it, so the town knows him as “Scary Larry.”

The twist? The constable and the community are majority black, and outcast Larry is white. Early in the work you realize this book is about the relationships between the two men, and all the racial dynamics that go along with that. Silas has to build a bridge back to his friend and at the same time, wants to clear Larry’s name. It’s a really good novel that delivers on the expectations established within the story, despite being dressed up as a mystery.

Literary Fiction, says the snob, “It’s about characters, you know. Unlike that genre fiction you plebes enjoy.” Trouble them not with things so odious as the mechanics of plot. It’s a common misconception about Science Fiction, Westerns, Mysteries, Thrillers, etc., but readers of those genres know that a good plot matters only so far as the characters drive said plot. Any story falls apart if the character motivations and behaviors are not true-to-life. Writers in those genres insist that the plot work according to expectations while at the same time the character journey be both inevitable and surprising.

What really troubles Literary authors about genre fiction, though, is that each genre has beats that readers have come to expect. The feeling is that they have that cultural sense we all have as to what makes stories work, and in the end, the story is what it wants to be. By avoiding the pigeonholing of genre, the reader knows not to expect all of the traditional beats, and might be open to receive a broader canvas of storytelling.

Genre writers typically are interested in “economy of style,” using only the necessary words to tell the story, prioritizing conciseness and avoiding unnecessary elaboration. Your average MFA student wouldn’t understand “economy of style” if Strunk & White slapped them in the face. Literary fiction is so-called because it’s about the words. It is prose-as-poetry. That’s fine if that’s what you’re after, and in the case of Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter, it delivers on its promises. In the case of Chenneville….

Hereafter follow spoilers.

Chenneville and its Promises

It isn’t accurate to say that Chenneville entirely fails to deliver on its promises. In order to understand where it fails, and what we can learn, we need to pick apart the narrative. There is a lot of gold in the experience.

From the outset, we learn there is bad news for John Chenneville, but he doesn’t know what it is. An uncle in New Orleans, writing to the doctor in Virginia, learns of John’s head wound and is told he must not be exercised by anything that may upset his recovery. The doctor is coy and plays it off that there is not bad news, but clearly there is something he has not been told. There is a mystery there that keeps us hanging on: what is the news John can’t be told?

Then when we learn that his sister and her family have been murdered, we have a great setup for a classic Western revenge plot. We know it’s going to take time for John to track down Dodd, but we’re along for the ride, because we empathize with the protagonist. So far so good. John has a couple run-ins with associates of Dodd. He must live off the land to survive, and avoid trouble with the locals.

The first sign of trouble with the story comes in John’s traveling identity. He goes to the trouble of having false discharge papers forged under an assumed name, yet at nearly every opportunity he introduces himself with his given name. The only time he bothers with the assumed identity is when checking into a hotel, when the papers are required.

It’s a wonder I didn’t give up on this novel then, but I was in too deep.

John proceeds along on his adventure, all the while showing he is a well-heeled gentleman. He treats people with respect and compassion despite his grim determination. At about the midpoint, John comes upon a telegrapher’s shelter in the middle of an Oklahoma snowstorm. The English telegrapher, Aubrey, takes him in, John demonstrates his knowledge of telegraphy from his time in the war, and they develop a friendship over tea, coffee and chess. John helps him restore a fallen line and clean and dress a deer.

Jiles even pulls a Blake Snyder (screenwriter, author of Save the Cat!) by having John save a hound and her puppies from starvation. There is something at his core that is at odds with his goal, because he is not a naturally violent man. This is rich soil for a compelling character journey, that ultimately remains unexplored. It is casually mentioned several times that he has a temper, though he only “loses it” once, amounting to some words that are harsher than he would have liked. That’s a temper?

He manages to unload the puppies on what seems to be a poor family with three girls which feels like an odd convenience in this setting. What family in this condition takes on three additional mouths to feed? The hound proves to be a useful companion for John on the road, acting as both scout and alarm. Another convenience is when he happens upon the attempted lynching of Lemuel, a young man who had been his nurse when convalescing in Virginia. He had accompanied John to St. Louis as he still had difficulties, then they parted ways. However, Lemuel was also a bit of a pickpocket, and had got himself into trouble in Nagadoches. John extricates Lemuel and returns the stolen property, then takes him as a sort of ward. Lemuel proves useful in a crucial way later.

In the cases of the hound, Lemuel, and the family, these appear to be clear instances of the author writing herself into a corner, realizing she needs a tool for the protagonist, and back-filling the setup. This happens all the time when writing fiction—especially mystery and thriller—but the goal is to make it appear natural. You don’t want the reader to see it happening, and in large part, readers who aren’t writers often will not.

There is little foreshadowing that John will reunite with Lemuel. In Chapter Two, Lemuel states he was thinking about going to Galveston, Texas. However, few readers will know just where Galveston is, or whether John is on the same road as Lemuel. If you sprinkle clues throughout, the reader’s subconscious begins to expect it. That’s how mysteries work, and it’s really just simple foreshadowing, an important tool for any and all genres. The fact that he encounters Lemuel at just the right moment right before he needs his skills absolutely smacks of author intrusion and convenience.

…it is set up as poorly as anything in this book. It’s a tactic of an amateur storyteller or the sign of a lazy editor, and Jiles has been at this too long to be an amateur.

Aubrey the telegrapher was in contact with another telegrapher in a city in Texas, a Victoria Reavis. We learn they can even send “private messages,” though the explanation is unclear. This provides an opportunity for John to receive messages at telegrapher’s offices along the way. John stops at a stage station on the Red River, and inside on a table is a book which Aubrey had in his possession, with a notation he had written inside the cover. There is also a telegraph message for John, inexplicably, under his real name. Aubrey has been murdered. It is a clue of Dodd’s trail.

John encounters U.S. Marshal Giddens, investigating Aubrey’s murder. He has tracked John from Fort Smith and knows his name already. Not very judicious of a man trying to murder someone. We are given no information as to how the Marshal tracked John, or how he learned his name. The Marshal is a narrative device added to give John that ticking time bomb that could go off at any moment; an additional layer of dramatic tension to drive the story forward. It’s a good addition, but executed clumsily.

John comes to a river and must find a place to cross, but it is night and he cannot see the depth. Conveniently, there comes a man across the river with a lantern who tells John where to cross. Somehow he realizes that this must be where people smuggle alcohol across the river. We are given no information as to how, and the text states the problem explicitly:

“Here! It’s safe!”

And then, on an odd whim, an unaccountable foreknowledge, John called out, “Dodd! Is that you?”

Silence. Only the night and the river.

The light disappeared. John instantly kicked Major forward….

It’s a wonder I didn’t give up on this novel here, but I was in too deep.

Yes, conveniently, John knows it’s Dodd. A man on the run for murder, who has committed a few crimes on the way, who knows he is being tracked, found time to settle in to a smuggling operation?! What follows is astounding and laughable. John comes upon a cabin near the river with a fireplace and clues to Dodd’s travels. He decides to tie up his horse and stay the night! Knowing the man he is tracking is a murderer and knows he is tracking him, doesn’t he think said murderer might…I don’t know…murder him in his sleep?!

You cannot have a pursuit story without the protagonist coming close to his quarry but failing to catch him, as in films such as The Fugitive or True Grit, but this is set up as poorly as anything in this book. The reason it is “odd” and “unaccountable” is because there is zero logic to it, and the author essentially admits that she spent zero time figuring out how to make this work better. It’s either a tactic of an amateur storyteller or the sign of a lazy editor, and Jiles has been at this too long to be an amateur.

Believe it or not, this is not the novel’s biggest sin.

When John arrives in Marshall, Texas, he comes upon the hotel where Ms. Reavis runs the telegraph office. John wants to get a room and clean up before introducing himself, but she is being accosted by an unrequited suitor and he goes to her aid, as dirty and stinky as the road has rendered him. She discerns quite quickly that he has a fever, and immediately demonstrates her maternal instinct by seeing to his recovery. He holes up in his room where she and a maid bring medicine and proper food, and they spend a few days getting to know each other.

It is the first time since finding out about his sister’s murder that John lets the grim facade crack—partly due to his vulnerability, but also the kindness and affection of Ms. Reavis. We understand that John and Victoria are good for each other, especially she for him, and we are meant to see this as John’s way out of his doomed course. If he continues after Dodd and kills him, then his life is forfeit as Giddens stands ready to imprison him, and John is resigned to his fate, for honor’s sake. If he stays with Victoria, he may recover his humanity.

On this point, it’s important to remember that throughout the story, John has consistently displayed his humanity, at odds with his mission. This is the core emotional dichotomy begging to be explored. Instead, the author seems to like this character so much that she doesn’t allow him to do things that make him unlikeable. If this were a stronger story, John would be gradually and consistently forced to contend with that dichotomy in order to survive and continue. We ought to be watching him slowly fall from grace as he slips into the kind of person who can kill for vengeance, and it’s not until fever incapacitates him that this angel of his imagination opens a window onto his soul and he catches a glimpse of redemption prior to the inevitable confrontation.

After he spends a few days with Victoria, John finds Lemuel in Nagadoches and takes him into his party. Lemuel proves his use to the story when they encounter some Illinois troops, with whom Dodd had served, and John talks to a man who knows him, but gives no answers after being suspicious of John’s curiosity. We know from proper foreshadowing that Lemuel is a thief, and in the night he manages to abscond with a letter from Dodd to the soldier John spoke to. Dodd sent the letter from San Antonio. John then buys Lemuel a horse, who is bound for Galveston as John heads for San Antonio, and sends the hound with Lemuel.

Several days later John arrives in San Antonio, only to be greeted by Giddens at the edge of town. Here it is: the last obstacle between he and Dodd. The inevitable confrontation between John and Giddens, prior to the inevitable confrontation between John and Dodd. The representation of justice stands between John and the realization of justice. It is a delicious dramatic irony that has worked in revenge stories since time immemorial.

If you’ve been following along with the tenor of this analysis, you can guess what happens.

He said, “You’re looking for Dodd.”

“That’s right. You’re looking for him too. I want you to get out of my way.” John didn’t care that Giddens had laid down his rifle, was standing with both hands and harmless. He cocked the revolver and brought up a load under the hammer. Click. Click.

“He’s dead.”

John sat without speaking for a long space. In this silence the night birds began their calling. The fire crackled.

Finally he said, “You’d better tell me more.”

“You don’t believe me,” said Giddens.

“I’m waiting.”

“He was killed in a bar fight a week ago. He was stabbed to death by a fiddler. I tell you the absolute truth, the fiddler killed him with his fiddlestick.”

AW, FIDDLESTICKS!

Good one, Paulette.

I shouldn’t have to tell you, whether a writer or a reader, what Ms. Jiles did wrong here. It is a crime against readers and God Himself to string people along for Twenty-Six chapters only to rob them of their payoff. This is Bill Buckner letting the ball go through his legs to lose the 1986 World Series for the Boston Red Sox. This is Greg Norman’s epic collapse in the 1996 Masters Tournament. This is Lucy yanking the football away from Charlie Brown’s foot.

As a writer, you must ensure that you make appropriate promises to the reader in your premise, which you are responsible enough to set up throughout your story, and are willing to pay off in your ending. Perhaps the worst part is the Protagonist has no ownership over his own story. He does not learn or grow in any significant way throughout his journey. In the end, the story’s momentum is stolen by an offscreen character with zero investment in the story. It is the inverse of deus ex machina, a phrase inherited from Greek drama, where the gods would intervene in the story and solve the problem for the hero. This is the fickle finger of fate rendering the entire story pointless. The buildup of taut tension into a string that could snap at any moment fizzles like a toy gun with the flag that says “Bang!”

Or more appropriately, “Fiddlesticks!”

Now, I’m not saying that John has to kill Dodd to make a good ending. I’m not suggesting John has to kill Giddens to get to Dodd. I’m not even saying John has to kill anyone. It is true that life often doesn’t go our way and robs us of the things we want in life. This is the clarion cry of the Lit Fic author: “We write about real life! Not that imaginary stuff!” That is fine, but storytelling should reflect real life, and say something about it, not exist merely as a literal representation of it.

Paulette Jiles does not write Westerns, in the genre sense, with all the traditional beats that entails. In fact, by the way it opens, it presents itself as a sort of Civil War story; a character drama about a man reconstructing his identity as a nation reconstructs its own. However, promises made to readers are not bound up simply in the classification of your story. Just because it is a Literary novel doesn’t mean it is devoid of reader expectations. The goal of your Protagonist determines your promises.

This was Jiles’ story to tell, and things don’t have to end tragically. It doesn’t have to be Shane or Unforgiven to be a satisfying ending. It is possible to rob John of his vengeance but give him back his soul in a way that gives him the ownership of his own story. How to do that is up to the author, but in this case, Paulette Jiles is guilty of dereliction of duty.

Takeaways

Here are the lessons we writers can learn from this:

Use Mystery. Early on, we saw Jiles use a little mystery, a lingering question that gave the story fuel for its initial forays.

Create Empathy. Readers will follow a protagonist with which they empathize. History will not remember Wyatt Earp strictly as a heroic figure, but most people empathize with what drove him to pursue and eliminate members of the largest and most deadly criminal gang in the Old West.

Find a Dramatic Dichotomy. In this case, John is a Gentleman with a natural compassion for the helpless, yet is tracking a man to kill him. Use opposing elements within your Protagonist, and bring them along gradually to the point that they become the person who is capable of achieving their goal, even if ultimately the “good side” wins.

Practice Proper Foreshadowing. Learn to sprinkle in clues of potential reveals or reunions so that the reader’s subconscious expects them, and they appear natural within the story.

Use the Ticking Timebomb. Marshal Giddens provided an additional layer of tension to drive John along in the story and also provide an element of danger. This is an extremely common and useful technique, no matter the story or genre.

Pay off Your Promises. Decide what sort of story you are telling, and make sure you understand what promises you are making to the reader. Do not give your protagonist a goal and then frustrate their realization of it by yanking the football away from Charlie Brown.

One might wonder if I feel like I wasted eleven hours and forty-nine minutes listening to Chenneville, and I do not. Paulette Jiles is a skilled writer, and there’s a lot to like in this book, which is probably why the faults stick out so freshly in my mind days later. I like John Chenneville, and Victoria Reavis, the hound Dixie, Lemuel, and even Marshal Giddens. It is a story with powerful drives and emotional experiences that sticks with you.

But even something with such poor execution at critical junctions in the story can be highly instructive—heck, even inspire a writer to go and do it better. As I said, there is a lot of gold to mine here.

I leave you with this quote from the end of Chenneville:

The world had changed completely, in a heartbeat. John’s lips parted as if to speak, but he didn’t; he felt a rage, a kind of cheated fury.

Same, John. Same.